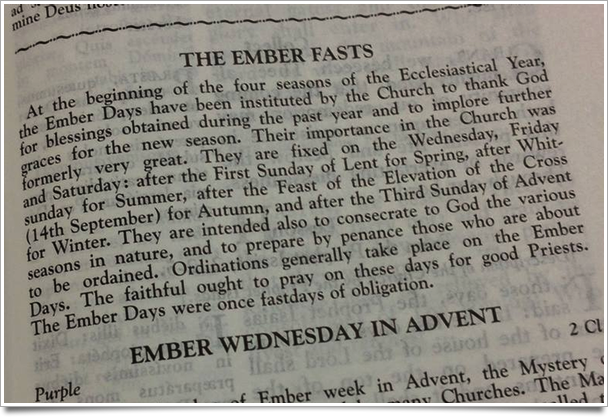

Ember Days, celebrated since the earliest days of the church, are unique in that they are rooted in the rhythm of the seasons. Traditionally, Ember days are days of prayers and fasting for bishops, priests and deacons, especially priests ordained during this season. It was a universal custom before Vatican II for all ordinations to happen during Ember Week. It is also customary to pray for a fruitful and bountiful harvest during the Fall Ember days. These times also give us a chance each season to reflect on our spiritual process, and in the fall we can especially reflect on the fruits we have born of our spiritual harvest over the past year.

Although fasting on Ember Days has become voluntary since the liturgical changes after Vatican II, many Catholics continue to take time each season to participate in fasting, abstinence and penance in union with the Church. As Leo the Great once said, “Devotion is all the more efficacious and holy, when the whole Church is engaged in works of piety, with one spirit and one soul. Everything, in fact, that is of a public character is to be preferred to what is private; and it is plain, that so much the greater is the interest at stake, when the earnestness of all is engaged upon it.”

- Ember Wednesdays – Fasting and Partial Abstinence

- Ember Fridays – Fasting and Abstinence

- Ember Saturday – Fasting and Partial Abstinence

Here’s more on the history of Ember days, from the Catholic Encyclopedia:

The purpose of their introduction, besides the general one intended by all prayer and fasting, was to thank God for the gifts of nature, to teach men to make use of them in moderation, and to assist the needy.The immediate occasion was the practice of the heathens of Rome. The Romans were originally given to agriculture, and their native gods belonged to the same class. At the beginning of the time for seeding and harvesting religious ceremonies were performed to implore the help of their deities: in June for a bountiful harvest, in September for a rich vintage, and in December for the seeding; hence their feriae sementivae, feriae messis, and feri vindimiales. The Church, when converting heathen nations, has always tried to sanctify any practices which could be utilized for a good purpose.At first the Church in Rome had fasts in June, September, and December; the exact days were not fixed but were announced by the priests. The “Liber Pontificalis” ascribes to Pope Callistus (217-222) a law ordering: the fast, but probably it is older. Leo the Great (440-461) considers it an Apostolic institution. When the fourth season was added cannot be ascertained, but Gelasius (492-496) speaks of all four. This pope also permitted the conferring of priesthood and deaconship on the Saturdays of ember week–these were formerly given only at Easter. Before Gelasius the ember days were known only in Rome, but after his time their observance spread. They were brought into England by St. Augustine; into Gaul and Germany by the Carlovingians. Spain adopted them with the Roman Liturgy in the eleventh century. They were introduced by St. Charles Borromeo into Milan. The Eastern Church does not know them.

Dom Gueranger gives great insight on the specific symbolism of the autumn Ember Days in his book The Liturgical Year:

For the forth time in her year, holy Church comes claiming from her children the tribute of penance, which, from the earliest ages of Christianity, was looked upon as a solemn consecration of the seasons. The historical details relative to the institution of the Ember-days will be found on the Wednesdays of the third week of Advent and of the first week of Lent; and on those same two days, we have spoken of the intentions which Christians should have in the fulfillment of this demand made upon their yearly service.The beginnings of the winter, sprint, and summer quarters were sanctified by the abstinence and fasting, and each of them, in turn, has received heaven’s blessing’ and now autumn is harvesting the fruits which divine mercy, appeased by the satisfactions made by sinful man, has vouchsafed to bring forth from the bosom of the earth, notwithstanding the curse that still hangs over her. (Gen.. iii. 17)The precious seed of what, on which man’s life mainly depends, was, confided to the soil in the season of the early frost, and, with the first fine days, peeped above the ground; at the approach of glorious Easter, it carpeted our fields with its velvet of green, making them ready to share in the universal joy of Jesus’ resurrection; then, turning into a lively image of what our souls ought to be in the season of Pentecost, its stem grew up under the action of the hot sun; the golden ear promised a hundred-fold to its master; the harvest made the reapers glad; and, now that September has come, it calls on man to fix his heart on that good God, who gave him all this store, Let him not think of saying, as that rich man did, after a plentiful harvest of fruits: “My soul! thou has much goods laid up for many years! Take thy rest, eat, drink, make good cheer!” And God said to that man: “Thou fool! this night do they require thy soul of thee; and whose shall those things be which thou has provided?” (St. Luke xiii. 16-21)

Blessed Jacopo de Voragine (A.D. 1230-1298), Archbishop of Genoa, wrote a collection of the stories of the Saints known as“Legenda Aurea” (Golden Legend) in which he expoains some of the fruits of the fasts and penances during these days.

The fasting of the Quatretemps, called in English Ember days, the Pope Calixtus ordained them. And this fast is kept four times in the year, and for divers reasons.For the first time, which is in March, is hot and moist. The second, in summer, is hot and dry. The third, in harvest, is cold and dry. The fourth in winter is cold and moist. Then let us fast in March which is printemps for to repress the heat of the flesh boiling, and to quench luxury or to temper it. In summer we ought to fast to the end that we chastise the burning and ardour of avarice. In harvest for to repress the drought of pride, and in winter for to chastise the coldness of untruth and of malice.The second reason why we fast four times; for these fastings here begin in March in the first week of the Lent, to the end that vices wax dry in us, for they may not all be quenched; or because that we cast them away, and the boughs and herbs of virtues may grow in us. And in summer also, in the Whitsun week, for then cometh the Holy Ghost, and therefore we ought to be fervent and esprised in the love of the Holy Ghost. They be fasted also in September tofore Michaelmas, and these be the third fastings, because that in this time the fruits be gathered and we should render to God the fruits of good works. In December they be also, and they be the fourth fastings, and in this time the herbs die, and we ought to be mortified to the world.The third reason is for to ensue the Jews. For the Jews fasted four times in the year, that is to wit, tofore Easter, tofore Whitsunside, tofore the setting of the tabernacle in the temple in September, and tofore the dedication of the temple in December.The fourth reason is because the man is composed of four elements touching the body, and of three virtues or powers in his soul: that is to wit, the understanding, the will, and the mind. To this then that this fasting may attemper in us four times in the year, at each time we fast three days, to the end that the number of four may be reported to the body, and the number of three to the soul. These be the reasons of Master Beleth.The fifth reason, as saith John Damascenus: in March and in printemps the blood groweth and augmenteth, and in summer coler, in September melancholy, and in winter phlegm. Then we fast in March for to attemper and depress the blood of concupiscence disordinate, for sanguine of his nature is full of fleshly concupiscence. In summer we fast because that coler should be lessened and refrained, of which cometh wrath. And then is he full naturally of ire. In harvest we fast for to refrain melancholy. The melancholious man naturally is cold, covetous and heavy. In winter we fast for to daunt and to make feeble the phlegm of lightness and forgetting, for such is he that is phlegmatic.The sixth reason is for the printemps is likened to the air, the summer to fire, harvest to the earth, and the winter to water. Then we fast in March to the end that the air of pride be attempered to us. In summer the fire of concupiscence and of avarice. In September the earth of coldness and of the darkness of ignorance. In winter the water of lightness and inconstancy.The seventh reason is because that March is reported to infancy, summer to youth, September to steadfast age and virtuous, and winter to ancienty or old age. We fast then in March that we may be in the infancy of innocency. In summer for to be young by virtue and constancy. In harvest that we may be ripe by attemperance. In winter that we may be ancient and old by prudence and honest life, or at least that we may be satisfied to God of that which in these four seasons we have offended him.The eighth reason is of Master William of Auxerre. We fast, saith he, in these four times of the year to the end that we make amends for all that we have failed in all these four times, and they be done in three days each time, to the end that we satisfy in one day that which we have failed in a month; and that which is the fourth day, that is Wednesday, is the day in which our Lord was betrayed of Judas; and the Friday because our Lord was crucified; and the Saturday because he lay in the sepulchre, and the apostles were sore of heart and in great sorrow.

More resources on Ember Days